Adrian Piper as African American Artist

American Art

Volume 20, Number 3 (Fall 2006)

DOI: 10.1086/511097

John P. Bowles, Associate Professor of African American Art History

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

African‐American artist Adrian Piper has repeatedly staged her own racial transformation in order to unsettle the racist attitudes of her artworks’ American viewers. Piper looks white but in her video installation Cornered, for example, she tells viewers, ”I’m black.” Over the course of the video the decision to call one’s self black or white becomes a moral issue rather than a simple matter of genetics or parentage. In the process, Piper casts the possibility of racial identity into doubt.

Piper’s self‐transformations figure the fears and fantasies that define the myth of American whiteness. Citing the unspoken “one drop” rule of racialized identity—according to which a person with only ”one drop” of African blood running through his or her veins is considered black—Piper challenges the viewer of Cornered: ”You are probably black. … What are you going to do?” Piper stages herself as an object for inspection, but in a way that ultimately reveals less about the artist than about the viewer’s own attitudes towards race. She identifies miscegenation and folkloric accounts of passing as the founding crisis for a pseudoscientific race consciousness in order to challenge Americans to take personal responsibility for the history of racism in the United States.

Adrian Piper once rebuked an an critic for declaring that it “is crucial to know” in approaching her work “that Piper is a black artist who can easily ‘pass’ for white.” In fact. Piper responded, “‘black’ and ‘white’ are among the terms my work critiques.” This statement would seem to preclude her an from being easily categorized as African American, yet that is exactly how most of it has been studied, largely because Piper has used herself and her own experiences with racism as the raw material for much of her artistic practice. In her 1988 video installation Cornered, for example, viewers watch as Piper tells them. “I’m black.” Over the course of the video, however, the decision to call one’s self black is reframed as a moral issue rather than a matter of genetics or parentage. In the process, Piper casts the possibility of racial identity into doubt. Why don’t most art critics notice?1

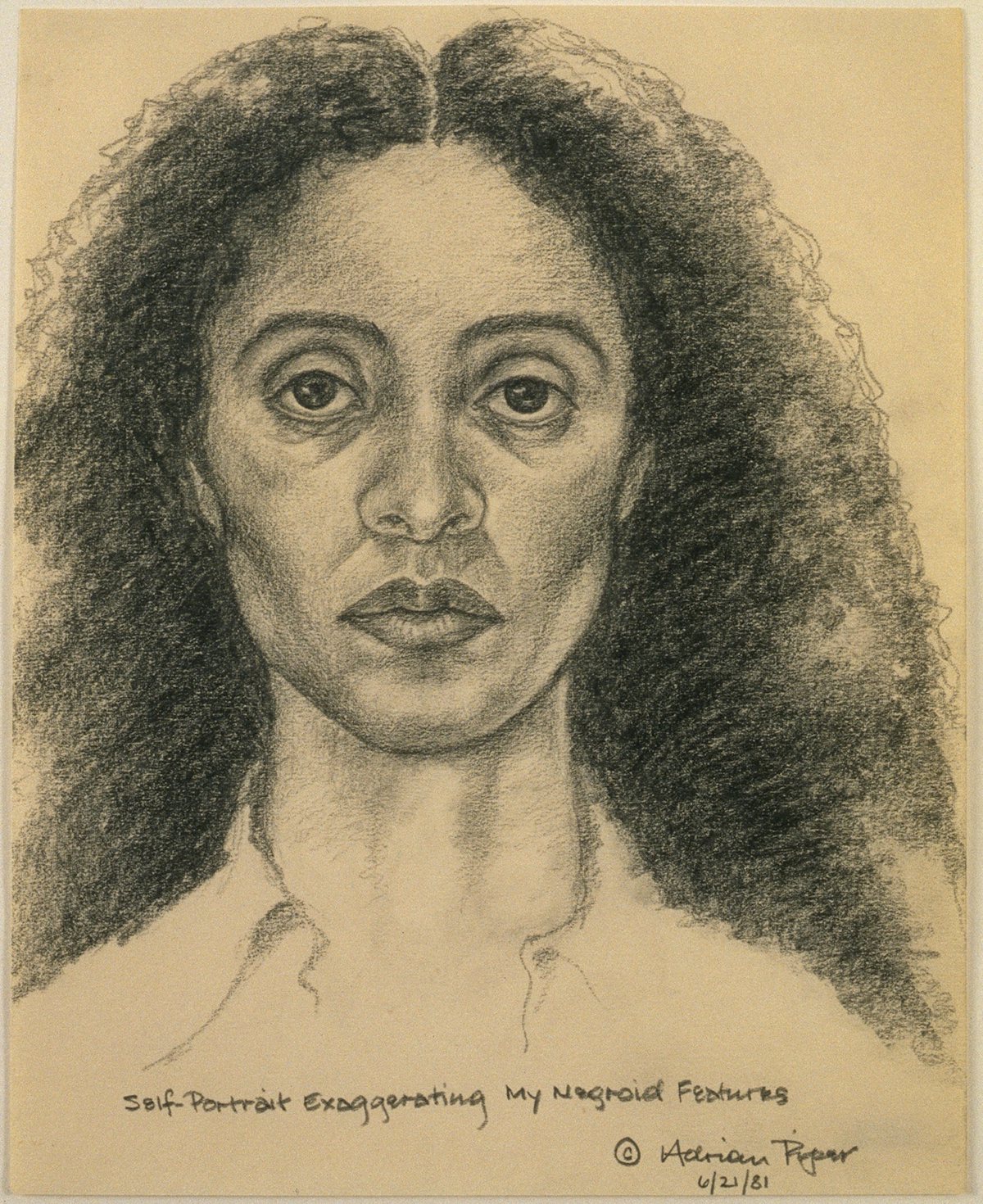

Since before 1972, when she first confronted matters of race directly in her Mythic Being Series, Piper has always marked the distinction between herself and the role she performs as artist in her theatricalized work. While she uses “personal content”—stories about her own experiences—in some of her work, these anecdotes are carefully chosen and presented tools used to make ideas concrete rather than to make her personal life and emotions the subject of her art. Nevertheless, art historians and critics frequently characterize Piper as an angry black woman whose work blames viewers for the lifetime of racist and sexist discrimination she has endured. Such accounts typically imply that Pipers work is divisive, because black audience members are expected to sympathize with the artist while white viewers may experience only guilt or outrage. Some of Piper’s critics respond by diagnosing her as the distraught victim, lashing out unfairly at liberal museumgoers who would otherwise take her side. Even writers more in tune with Piper’s project interpret her work as autobiography. In the 1970s, for example, feminist art critics Lucy Lippard and Cindy Nemser both explained Piper’s Mythic Being as the manifestation of the artist’s “male ego,” despite formal aspects that cast the series as a critical and self-conscious performance of race, gender, sexuality, and class.2

In The Mythic Being: I/You (Her) of 1974, Piper transforms her appearance over a series of ten photographs of herself, taken in junior high school, beside another young woman, a classmate and friend. As with most of the Mythic Being photographs. Piper has added comic-strip-style thought bubbles in the I/You (Her) sequence by drawing, painting, and writing directly on the surfaces of the photographs. In this sequence, her face is slowly darkened while her companions remains unchanged. Pipers features are altered and exaggerated; she acquires sunglasses and a mustache; her hair grows into what she…

Read or purchase the article here.