Cracking The Code

The New Yorker

2015-05-14

Jesmyn Ward, Associate Professor of English

Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana

Illustration by Rebekka Dunlap

I had always understood my ancestry to be a tangle of African slaves, free men of color, French and Spanish immigrants, British colonists, Native Americans—but in what proportion?

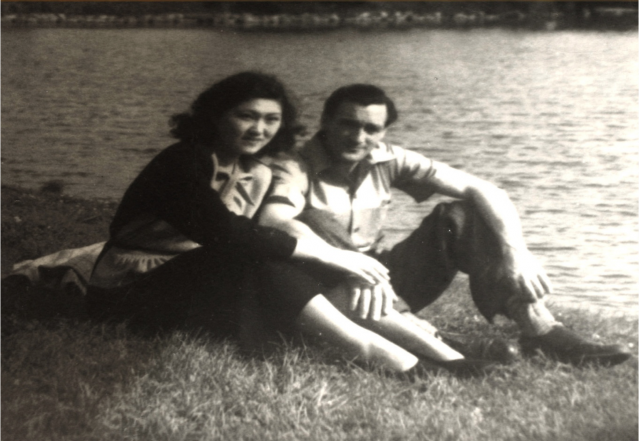

When my father moved to Oakland, California, after Hurricane Camille wrecked the Mississippi Gulf Coast, in 1969, strangers he encountered from El Salvador and Mexico and Puerto Rico would spit rapid-fire Spanish at him, expecting a reply in kind. “Are you Samoan?” a Samoan asked him once. But my father, with his black, silky hair that curled into Coke-bottle waves at the ends, skin the color of milky tea, and cheekbones like dorsal fins breaking the water of his face, was none of these things. He attended an all-black high school in Oakland; in his class pictures, his is one of the few light faces. His hair is parted in the middle and falls away in a blowsy Afro, coarsened to the right texture by multiple applications of relaxer.

My father was born in 1956 in Pass Christian, a small Mississippi town on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, fifty miles from New Orleans. He grew up in a dilapidated single-story house: four rooms, with a kitchen tacked onto the back. It was built along the railroad tracks and shook when trains sped by; the wood of the sloped floor rotted at the corners. The house was nothing like the great columned mansions strung along the man-made beach just half a mile or so down the road, houses graced with front-facing balconies so that the wealthy white families who lived in them could gaze out at the flat pan of the water and the searing, pale sand, where mangrove trees had grown before they’d bulldozed the land.

Put simply, my father grew up as a black boy in a black family in the deep South, where being black, in the sixties, was complicated. The same was true in the eighties, when I was growing up in DeLisle, a town a few miles north of Pass Christian. Once, when I was a teen, we stood together in a drugstore checkout line behind an older, blondish white woman. My father, an inveterate joker, kept shoving me between my shoulder blades, trying to make me stumble into her. “Daddy, stop,” I mouthed, as I tried to avoid a collision. I was horrified: Daddy’s going to make me knock this white woman over. Then she turned around, and I realized that it was my grandaunt Eunice, my grandmother’s sister—that she was blood. “I thought you were white,” I said, and she and my father laughed.

Coastal Mississippi is a place where Eunice—a woman pale as milk, with blond hair and African heritage—is considered, and considers herself, black. The one-drop rule is real here. Eunice wasn’t allowed on the beaches of the Gulf Coast or Lake Pontchartrain until the early seventies. The state so fiercely neglected her education that her grandfather established a community school for black children. Once Eunice graduated, after the eighth grade, her schooling was done. She worked in her father’s fields, and then as a cleaning woman for the white families in their mansions on the coast. On the local TV station, she watched commentators discuss what it meant to be a proper Creole, women who were darker than her asserting that true Creoles have only Spanish and French ancestry. Theirs was part of an ongoing attempt to write anyone with African or Native American heritage out of the region’s history; to erase us from the story of the plantations, the swamps, the bayou; to deny that plaçage, those unofficial unions, during the time of anti-miscegenation laws, between European men and women of African heritage had ever taken place…

Read the entire article here.