Biracial/Bicultural Identity in the Writings of Sui Sin Far

MELUS

Volume 26, Number 2 (Summer 2001)

pages 159-186

Vanessa Holford Diana, Professor of English

Westfield State Unviversity, Westfield, Massachusetts

At the turn into the twentieth century, American culture witnessed related literary and political shifts through which marginalized voices gained increased strength despite the severe racism that informed US laws and social interaction. Many authors and literary critics saw connections between literary content and social influence. For example, in Criticism and Fiction (1891), William Dean Howells, proponent of nineteenth-century American realism, warns readers to avoid sentimental or sensational novels, which he claims “hurt” by presenting “idle lies about human nature and the social fabric.” He reminds us that “it behooves us to know and to understand” our people and our social context “that we may deal justly with ourselves and with one another” (94-95). He argues that the writer of fiction is obligated to write that which is “tree to the motives, the impulses, the principles that shape the life of actual men and women” in the US (99). His is both a demand for aesthetic standards in fiction and an insistence that the failure to achieve “true” representations of American people will result in the disintegration of national humanity and, consequently, of national unity. The irony of Howells’ standards is that despite this impulse toward national unification, his own tenets of American realism have for years served to exclude from the canon those writers who were greatly interested in creating “tree” representations of American characters in order to promote a society in which Americans could finally “deal justly with ourselves and with one another.”

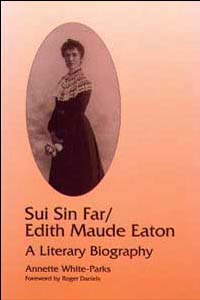

One artist who wrote with the goal of creating an America where we would “deal justly” with one another was turn-of-the-century Eurasian journalist and fiction writer Sui Sin Far. In an essay entitled “The Chinese in America,” Sui Sin Far laments western literary depictions of the Chinese that portray them as “unfeeling” and “custom-bound.” “[F]iction writers seem to be so imbued with [these] ideas that you scarcely ever read about a Chinese person who is not a wooden peg,” she protests (234). She argues that in general the Chinese “think and act just as the white man does, according to the impulses which control them. They love those who love them; they hate those who hate; are kind, affectionate, cruel or selfish, as the case may be” (234). Through this comparison Sui Sin Far decenters whiteness as the standard of what is “human,” a move that is in fact central to much of her work, as Annette White-Parks has argued in an essay entitled “A Reversal of American Concepts of `Otherness.'” Sui Sin Far’s characters are often people who resist assimilation, and through them she depicts Chinese communities in North America populated with characters rich and diverse in their complexity. This study builds on White-Parks’ conclusions by exploring the role of genre manipulation in Sui Sin Far’s literary and political innovations. In addition, I will argue that Sui Sin Far’s specific focus on the position of biracial and bicultural individuals (both in autobiographical and fictional representations) is a major strategy in her redefinition of “race” as a category in American thought.

Like Howells, Sui Sin Far demands in fiction a truthful depiction of Americans; her rewriting, however, represents an adaptation of mainstream realism because it focuses on Americans who had, before she wrote, little voice in American literature. Amy Ling characterizes Sui Sin Far’s writing as among one of “the earliest attempts by Asian subalterns to speak for themselves” (“Reading” 70). Offering alternative perspectives on American identity and culture, Sui Sin Far, along with many of her contemporary writers of color, actively challenged mainstream readers’ preconceptions and contributed to a social climate in which increasing numbers of writers of color made their voices heard in print. In doing this, she engaged a shift from margin to center that posited the “Other” as speaking voice, thereby dramatizing the injustices that plagued race relations in North America.

Current critical approaches to turn-of-the-century American realism locate within the project of national identity-building a trend of revolutionary revision, through which marginalized writers disclose the inequalities in US culture and show the establishment of a unified and “true” American identity to be impossible while racism continues to enforce social exclusion and hierarchy. At the same time, literary critics are rethinking the genre of sentimental romance to better understand the ways in which women writers employed and subverted this genre and the rhetorical devices it employs in order to dramatize (and put an end to) social injustice. Drawing from elements of both realism and sentimental romance, Sui Sin Far uses short stories, articles, and essays to pioneer the act of self-representation for a people who existed in late nineteenth-century mainstream American imagination and literature as uncivilized, heathen foreigners. In her short stories, articles, and autobiographical essays Sui Sin Far achieves far more than her modestly stated goal “of planting a Eurasian thoughts into Western literature” (288). Her fiction challenges and shifts socially constructed definitions of Chineseness, constructions that enact what Judith Butler would term the “regulatory norms” that inflict exclusion upon marginalized peoples.

A focus on Sui Sin Far’s depiction of Eurasian characters and on the subject of interracial marriage illustrates her multifaceted understanding of the crisis in US race relations. Through the treatment of these subjects, she enacts a revolutionary revisioning of race differences. The stories found in Mrs. Spring Fragrance and Other Writings, including “Pat and Pan,” “Its Wavering Image,” along with excerpts from “The Story of One White Woman who Married a Chinese,” “Her Loving Husband,” and Sui Sin Far’s autobiographical essay, “Leaves from the Mental Portfolio of an Eurasian,” exemplify the artistic and psychological complexity of Sui Sin Far’s treatment of the biracial character and of interracial marriage. In particular, by addressing these themes, Sui Sin Far deconstructs Orientalism by dramatizing the destructive ways in which North American culture defines the Chinese as inhuman “Other” in order to prevent interracial understanding and maintain profitable power structures. Sui Sin Far’s fiction and essays illustrate the lengths to which members of the dominant culture will go to preserve a notion of racial purity based on hatred and ignorance, and she explores the terrible effects that racism has on its victims…

Purchase the article here.