All the parts of myself…Posted in Excerpts/Quotes on 2013-11-09 15:10Z by Steven |

For similar reasons, The Boondocks also critiques one of the mainstays of mixed race representation: the obligatory rehearsal of one’s multiracial family tree. Replacing calls for social justice or racial equity, the most often repeated goal of “mixed race rights” is merely to “name all the parts of myself.” The rhetorical or graphic display of the family tree (almost de rigueur in the growing genre of mixed race narratives) participates in a racial gaze that can interrupt political reflection. For Jazmine and her family, description has come to stand in for politics, genealogy substituting for political discussions of the body politic. The family tree is paraded as revelatory and socially transforming fact. It has come to serve as proxy for social change, in which representing one’s family tree has become a political end in itself. The exercise of those rights often amounts to making identity a category of genealogical documentation, documentation which, to the extent that it is complacently represented as an end in itself whose social good is somehow self-evident, obscures identity as social index and mode of analysis. When Huey asks Jazmine, “OK… if you’re not black, then what are you, hmmm?” she responds dutifully with a list documenting down to the fraction her ethnic racial portfolio: “My mother is one-quarter Irish, one-quarter Swedish, and one-half German, and on my father’s side is part Cherokee, and my grandfather is mostly French, I think, because he’s originally from Louisiana, and his father was from Haiti I believe, which makes me…” Huey intervenes: “Which makes you as black as Richard Roundtree in ‘Shaft in Africa’” (A Right to Be Hostile 15). Huey disparages not so much her mixed genealogy as the idea that a recapitulation of ethnic and national descent really says anything meaningful about racial identity. At the very least, he suggests, her genealogy is neither progressive nor has sufficient explanatory force. Rather, her accounting retroactively ratifies the idea of racially homogeneous categories and national identities by suggesting that each parent’s race or ethnicity is unitary.

Her laundry list also collapses blood and nation and then fractionalizes both—how else can the notion of “one-quarter Swedish” make sense—and looks less like the new millennial model of post-race and more like an uncritical revival of classic nineteenth-century positivist racialism. Huey interrupts her—and the discourse itself—by insisting instead on the political nature of racial identity: he teases her by saying, “I understand, Jazmine. I’m mixed too.” We see an up-close shot of her face, which lights up as she says hopefully, “You are?” only to have him sarcastically claim, much to her disappointment, to be “part Black, part African, part Negro, and part colored.” Significantly, his designations do not pretend to be descriptive; they all carry heavy historical and political implication. He then walks off wailing, “Poor me. I just don’t know where I fit in,” as she cries after him (again): “You’re making fun of me!” (16). Of course, Huey is making fun of Jazmine in this exchange. However, his send-up is social critique to the degree that it does not concede the reduction of racial identity to the sum of one’s parts; he thinks of race not in terms of blood but in relation to representation. Shaft in Africa, after all, is late in the series of 1970s campy sex-and-adventure Blaxploitation films. Huey’s invocation of the hyper-blackness represented in the Blaxploitation genre of film is a spoof of them—he is concerned not with black authenticity but with cultural figurations of blackness. Race, for McGruder, is always cast as a matter of historical consciousness, social play, and political engagement. This perspective is reinforced in his comments on the racial status of Barack Obama, when he notes, “We all share the common experiences of being Black in America today—we do not all share a common history.” In such scenes, The Boondocks replaces mere optic confirmation of race with black cultural performance and historical citation as more useful markers of racial identity. His coherent sense of “Black” is historically informed, historically evolving, and historically heterogeneous in both community composition and cultural practice.

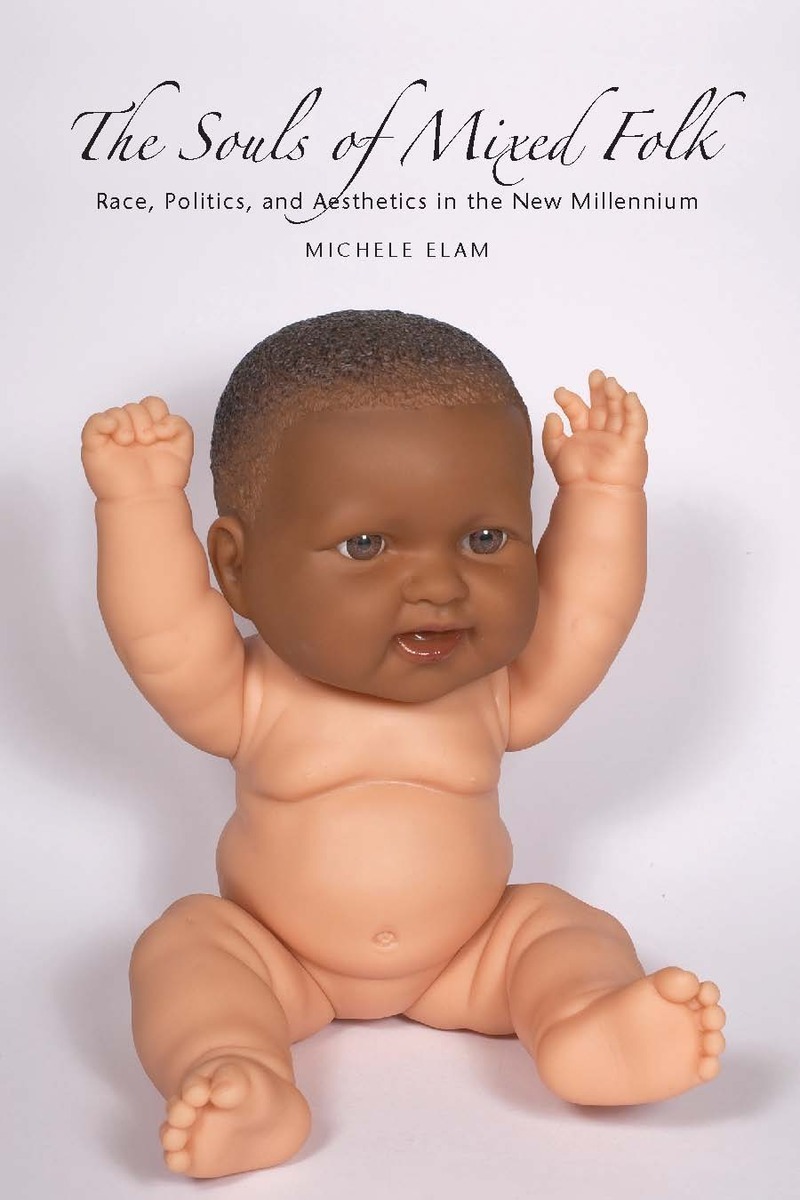

Michele Elam, The Souls of Mixed Folk: Race, Politics, and Aesthetics in the New Millennium (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2011), 69-70.