A Hidden Caribbean Revolution? Race and Revolution in Venezuela, 1789-1817Posted in Caribbean/Latin America, History, Media Archive on 2018-05-16 23:05Z by Steven |

A Hidden Caribbean Revolution? Race and Revolution in Venezuela, 1789-1817

Age of Revolutions

2018-05-14

Frédéric Spillemaeker, Researcher (Casa de Velázquez (École des Hautes Études Hispaniques et ibériques, EHEHI)) and Ph.D. Candidate

École des Hautes des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS)

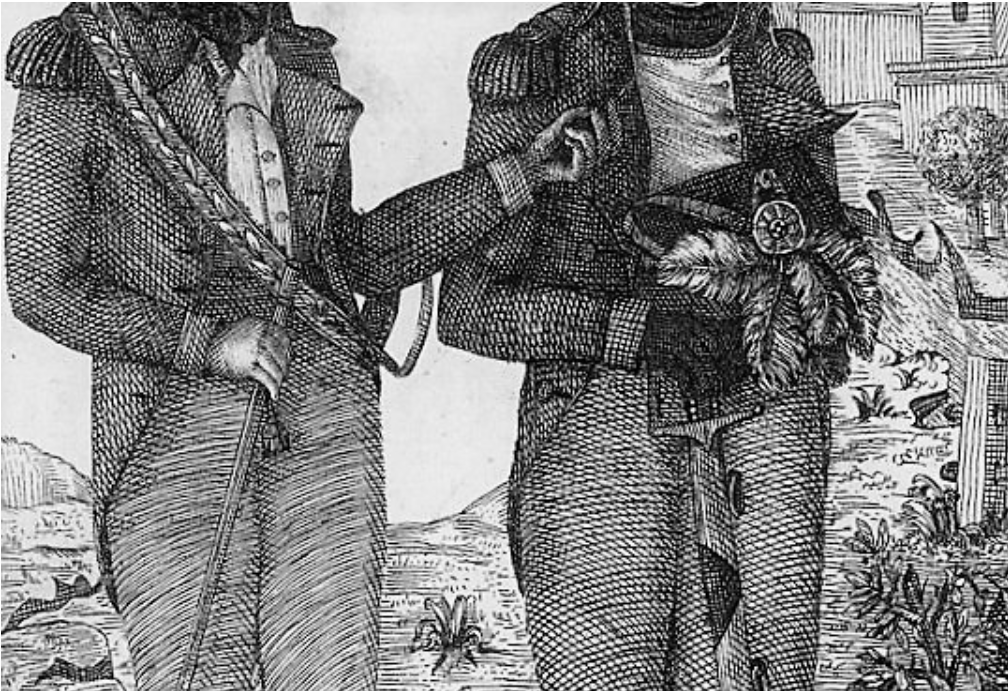

Manuel Carlos Piar. Obra de Pablo W. Hernández. |

The wave of revolutionary sentiment from the 1790s to Independence questioned the social and racial inequalities that divided colonial Venezuela. The majority of the Venezuelan population was Pardo, a mixed-race people of African and European descent who were considered legally inferior to Europeans and Creoles. While pardos could bear arms and organize in militias, they only ascended to the grade of captain. Hence, most pardo militias remained under command of Mantuanos – white colonels and members of the landed ruling class. When colonial order was challenged by Amerindians seeking to recover their lands and slaves pursuing freedom, a large mass of armed pardos mobilized in demand of equality. The 1790s revolutions in the Greater Caribbean, and later, the Latin American Independence Wars beginning in 1810, scrambled the existing socio-racial structure of domination in Venezuela, at least in the domain of the army, with pardo leaders like Jean-Baptiste Bideau and Manuel Piar…

In August 1793, the Revolution led by Toussaint Louverture, enabled the abolition of slavery in Saint Domingue.[1] A few months later, on 16 Pluviôse An II (February 4, 1794), the French Convention extended the abolition decree to all French colonies. By June 1794, when Victor Hugues took over Guadeloupe, former slaves had become soldiers in defense of revolutionary values. This was the beginning of a cycle of victories for the alliance between France, free people of color, and emancipated slaves.[2] In the island of Trinidad, formerly part of Venezuela, a battle confronted the alliance of French and Afro-Antilleans against the English on May 8-9, 1796. Among the French officers was Jean-Baptiste Bideau, a “mulâtre” from Sainte-Lucie.[3] In spite of the defeat and the English seizure of the island in February 1797, slave uprisings erupted throughout Venezuela. Armed slaves mobilized in Carupano and in Rio Caribe in 1798,[4] and a suspected pardo plot was unveiled in Barcelona in 1801.[5] Back in Saint Domingue, now named Haiti, the revolution resisted Napoleon’s slavery restoration attempt and ultimately declared its Independence in 1804…

Read the entire article here.