Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist

Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University

2001 Campus Drive

Durham, North Carolina 27705

On view 2014-01-30 through 2014-05-11

ABOUT

Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist, the first retrospective of the American artist’s paintings in two decades, will originate at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University on January 30, 2014, starting a national tour.

SO MODERN, HE’s CONTEMPORARY

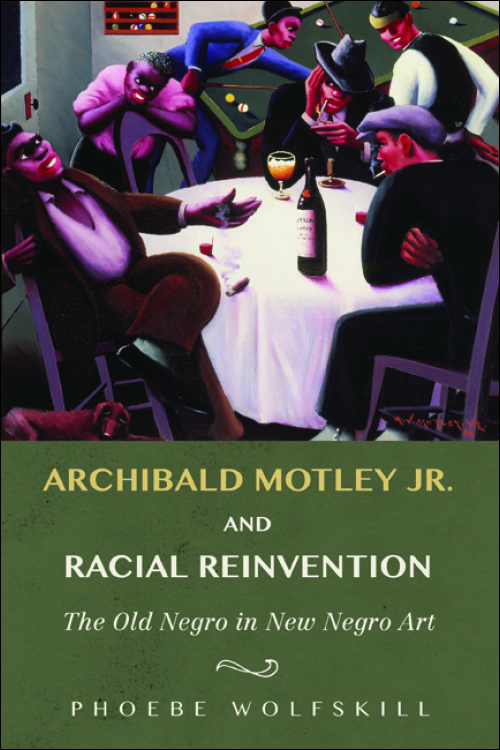

Motley is one of the most significant yet least visible 20th-century artists, despite the broad appeal of his paintings. Many of his most important portraits and cultural scenes remain in private collections; few museums have had the opportunity to acquire his work. With a survey that spans 40 years, Archibald Motley introduces the artist’s canvases of riotous color to wider audiences and reveals his continued impact on art history.

FOR THE FIRST TIME AT THE NASHER MUSEUM

Archibald Motley includes 42 works from each period of Motley’s lifelong career, from 1919 to 1960. Motley’s scenes of life in the African-American community, often in his native Chicago, depict a parallel universe of labor and leisure. His portraits are voyeuristic but also genealogical examinations of race, gender and sexuality. Motley does not shy away from folklore fantasies; he addresses slavery and racism head on. The exhibition also features his noteworthy canvases of Jazz Age Paris and 1950s Mexico. Significant works will be presented together for the first time.

“We are extremely proud to present this dazzling selection of paintings by Archibald Motley, a master colorist and radical interpreter of urban culture,” said Sarah Schroth, Mary D.B.T. and James H. Semans Director of the Nasher Museum. “His work is as vibrant today as it was 70 years ago; with this groundbreaking exhibition, we are honored to introduce this important American artist to the general public and help Motley’s name enter the annals of art history.”

THE MAN, THE ARTIST

Archibald John Motley, Jr. (1891-1981), was born in New Orleans and lived and worked in the first half of the 20th century in a predominately white neighborhood on Chicago’s Southwest side, a few miles from the city’s growing black community known as “Bronzeville.” In his work, Motley intensely examines this community, carefully constructing scenes that depict Chicago’s African American elites, but also the worlds of the recently disembarked migrants from the South and other characters commonly overlooked.

In 1929, Motley won a Guggenheim Fellowship that funded a year of study in France. His 1929 work Blues, a colorful, rhythm-inflected painting of Jazz Age Paris, has long provided a canonical picture of African American cultural expression during this period. Several other memorable canvases vividly capture the pulse and tempo of “la vie bohème.” Similar in spirit to his Chicago paintings, these Parisian canvases extended the geographical boundaries of the Harlem Renaissance, depicting an African diaspora in Montparnasse’s meandering streets and congested cabarets.

In the 1950s, Motley made several lengthy visits to Mexico, where he created vivid depictions of life and landscapes. He died in Chicago in 1981.

ON THE ROAD

Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist opens at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University and will travel to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas (June 14–September 7, 2014); the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (October 19, 2014–February 1, 2015); the Chicago Cultural Center (March 6–August 31, 2015) and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (Fall 2015).

For more information, click here.