Getting In and OutPosted in Articles, Book/Video Reviews, Literary/Artistic Criticism, United States on 2017-06-26 19:12Z by Steven |

Harper’s Magazine

July 2017

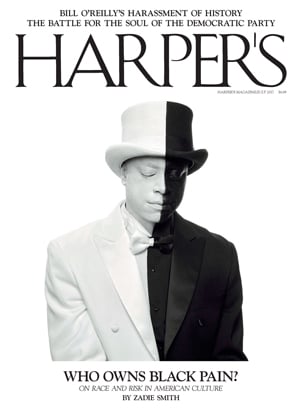

Who owns black pain?

Discussed in this essay:

Get Out, directed by Jordan Peele. Blumhouse Productions, QC Entertainment, and Monkeypaw Productions, 2017. 104 minutes.

Open Casket, by Dana Schutz. 2017 Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. March 17–June 11, 2017.

You are white—

yet a part of me, as I am a part of you.

That’s American.

Sometimes perhaps you don’t want to be a part of me.

Nor do I often want to be a part of you.

But we are, that’s true!

As I learn from you,

I guess you learn from me—

although you’re older—and white—

and somewhat more free.

—Langston Hughes

Early on, as the opening credits roll, a woodland scene. We’re upstate, viewing the forest from a passing car. Trees upon trees, lovely, dark and deep. There are no people to be seen in this wood—but you get the feeling that somebody’s in there somewhere. Now we switch to a different world. Still photographs, taken in the shadow of public housing: the basketball court, the abandoned lot, the street corner. Here black folk hang out on sun-warmed concrete, laughing, crying, living, surviving. The shots of the woods and those of the city both have their natural audience, people for whom such images are familiar and benign. There are those who think of Frostian woods as the pastoral, as America the Beautiful, and others who see summer in the city as, likewise, beautiful and American. One of the marvelous tricks of Jordan Peele’s debut feature, Get Out, is to reverse these constituencies, revealing two separate planets of American fear—separate but not equal. One side can claim a long, distinguished cinematic history: Why should I fear the black man in the city? The second, though not entirely unknown (Deliverance, The Wicker Man), is certainly more obscure: Why should I fear the white man in the woods?…

…We have been warned not to get under one another’s skin, to keep our distance. But Jordan Peele’s horror-fantasy—in which we are inside one another’s skin and intimately involved in one another’s suffering—is neither a horror nor a fantasy. It is a fact of our experience. The real fantasy is that we can get out of one another’s way, make a clean cut between black and white, a final cathartic separation between us and them. For the many of us in loving, mixed families, this is the true impossibility. There are people online who seem astounded that Get Out was written and directed by a man with a white wife and a white mother, a man who may soon have—depending on how the unpredictable phenotype lottery goes—a white-appearing child. But this is the history of race in America. Families can become black, then white, then black again within a few generations. And even when Americans are not genetically mixed, they live in a mixed society at the national level if no other. There is no getting out of our intertwined history…

Read the entire review here.