Black and Jewish: Language and Multiple Strategies for Self-Presentation

American Jewish History

Volume 100, Number 1, January 2016

pages 51-71

DOI: 10.1353/ajh.2016.0001

Sarah Bunin Benor, Associate Professor of Contemporary Jewish Studies

Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, Los Angeles, California

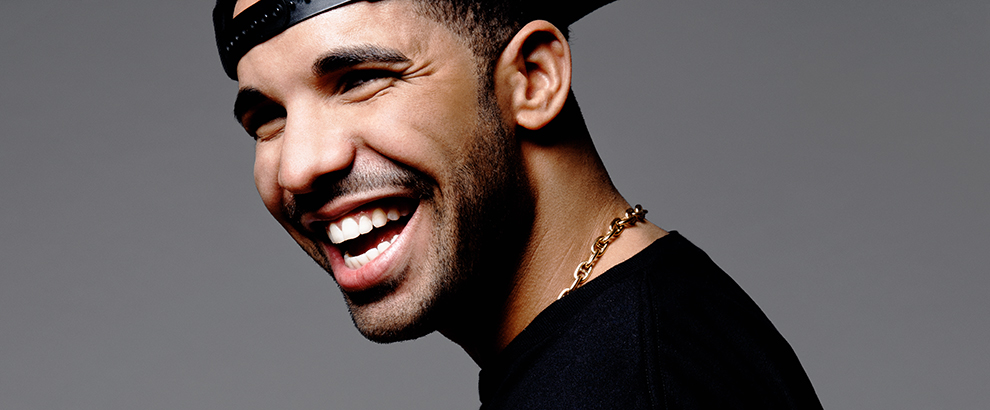

In January 2014, hip-hop star Drake hosted “Saturday Night Live” (SNL), opening with a skit about his black Jewish identity. In this skit, which takes place at his bar mitzvah reception, language is central to the comedy: Drake’s white Jewish mother has an exaggerated New York-sounding accent, and she uses Hebrew and Yiddish words — “tuchuses,” “oy vey,” “goy,” and “mazel tov.” His black dad uses features of African-American English, like /th/ sometimes pronounced as /d/, and he jokingly highlights his lack of knowledge of Drake’s mom’s Jewish language: “Torah, aliyah — man, I know dose girls, I met them on da road.” When Drake enters, he greets his relatives with words associated with each group: “To my mom’s side of the family I say, ‘Shabbat shalom,’ and to my dad’s side, I say ‘Wasssupppp.’” Drake proceeds to sing and rap about being black and Jewish, incorporating strains of “Hava Nagila” and hip hop, and highlighting stereotypical characteristics and linguistic features of both groups: “I play ball like LeBron [James], and I know what a W-2 is. Chillin’ in Boca Raton with my mensch Lenny Kravitz [another black Jew], the only purple drink we sip is purple Manischewitz. At my show you won’t simply put your hands in the air; we can also raise a chair or recite a Jewish prayer… I eat… knishes with my bitches … I celebrate Hanukkah, date a Rianika… You’re Jewish and black and you’re — challah!”

The juxtaposition of stereotypical linguistic, culinary, and celebratory practices associated with African Americans and Jews is funny to the audience because of the incongruence: The audience is not used to observing these practices in the same room, let alone the same individual. In addition, the presentation is intelligible as indexing black Jewishness because people outside the black and Jewish communities associate these practices with black people and Jewish people, respectively. Even if Drake does not use cultural combinations like these in his everyday life, he (along with the SNL production team) considers them appropriate for a parodic performance of his black Jewish identity.

Drake’s performance represents a growing phenomenon: individuals presenting themselves to the public as black Jews through comedy, performance art, interviews, and memoirs. In all of these “performances” (the term used broadly to refer to any speech act intended for consumption by a large audience), language plays an important role in how speakers align themselves with African Americans, with Jews, or with both. In this paper, I analyze nine such performances, focusing on the nine individuals’ use of linguistic features associated with Jews and with African Americans. This analysis points to the importance of language in self-presentation, as well as to the diversity of black Jews.

Black Jews

First, a bit of background on black Jews and on language associated with both groups. A common origin of black Jews is the union of a white Jew and a black non-Jew (sometimes involving the conversion of one spouse). This is the case for Drake and five of the nine individuals featured in the analysis below. The biracial children of these unions are sometimes raised with Judaism as their religion, sometimes with a Jewish cultural identity, and sometimes with no Jewish identity or practice. Another common origin occurs when white Jewish parents adopt children from Africa or from African-American birth parents and raise them as Jews, sometimes officially converting them. In addition to these individuals who grow up black and Jewish, many black people adopt Judaism later in life. Some of these converts are attracted to Judaism for spiritual or theological reasons, and others for social, cultural, or communal reasons, such as having Jewish friends or partners. Smaller numbers of black Jews immigrated to the United States from Jewish communities in Ethiopia, Uganda, Nigeria, and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa. Finally, some black Jews are descendants of black people who converted to Judaism or who had children with white Jews several generations ago. In some families, Judaism goes back to the days of slavery, when black slaves sometimes adopted the religion of their white owners, a very small percentage of whom were Jewish.

Some discussions of…

Read or purchase the article here.