Eric Nguyen Reviews Genaro Kỳ Lý Smith’s ‘The Land South of the Clouds’Posted in Articles, Asian Diaspora, Book/Video Reviews, Media Archive, United States on 2017-03-09 02:53Z by Steven |

Eric Nguyen Reviews Genaro Kỳ Lý Smith’s ‘The Land South of the Clouds’

diaCRITICS: Covering the arts, culture and politics of the Vietnamese at home and in the diaspora

2017-03-06

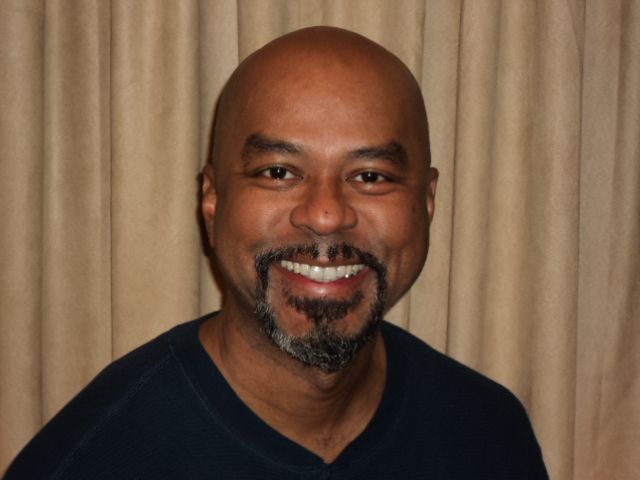

Author Genaro Kỳ Lý Smith.

diaCRITIC Eric Nguyen reviews The Land South of the Clouds, Genaro Kỳ Lý Smith’s newest fiction novel.

Genaro Kỳ Lý Smith returns to familiar territory in his second book, The Land South of the Clouds. Readers of his previous book, The Land Baron’s Sun, will be acquainted with many of the subjects here: the Vietnam War, the loss of homeland, and even a character, Lý Loc, the elderly patriarch based on Smith’s grandfather who sees his old ways of life dramatically changed when the Communists come to power. But whereas Smith’s first book largely focused on life in Vietnam in the aftermath of war, The Land South of the Cloud explores what life is like for those who left.

The book opens up in Los Angeles. It is June 1979. The Iran hostage crisis is only a few months away and so is the release of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now in American theaters and ten-year-old Long-Vanh is watching his mother, Vu-An, leave as her husband, Wil, sleeps. “You can tell them I’m dead,” she says before asking Long-Vanh to keep her departure a secret and boarding a cab. Torn between loyalties, Long-Vanh races to his sleeping father but is interrupted by the unexpected return of his mother. It was a practice run, she says, before telling him again, “Don’t tell your Dad.”…

…The Land South of the Cloud is frank in its depiction of being biracial in a country that often sees only black and white when it comes to race. Like the nameless narrator of James Weldon Johnson’s The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, Long-Vanh isn’t so much as straddled between two worlds of race as alienated by them. Unlike Johnson’s narrator, though, Long-Vanh can’t pass as one race or the other. The result is an experience marked by both outsider status and shame. For Long-Vanh this means being treated as an anomaly at worst or an exotic object at best. As a child, he is called a “yellow nigger” by other Vietnamese kids. As an adult, Long-Vanh notes:

Women were always curious about my kind, and they wanted to know what it was like to sleep with someone like me. To them, I was something of a curiosity, someone they could lay claim to, like a token, and say, “I’ve slept with one of them.”

Long-Vanh is never truly comfortable with who he is…

Read the entire review here.