Driven by Love or Ambition, Slipping Across the Color Line Through the AgesPosted in Articles, History, Media Archive, Passing, United States on 2015-06-29 20:33Z by Steven |

Driven by Love or Ambition, Slipping Across the Color Line Through the Ages

The New York Times

2015-06-28

Clarence King, a Yale-educated white man who worked as a geologist in the 1800s and dined at the White House, lived a secret life as James Todd, a black train porter with a wife and five children in Brooklyn. |

The railroad carried him to the hot springs of Arkansas, the copper mines of Montana and the gold fields of the Pacific Northwest. Weary, lonesome and ailing, he sent letters of love and longing to his wife in New York City.

“I can see your dear face every night when I lay my head on the pillow,” he wrote. “I think of you and dream of you, and my first waking thought is of your dear face and your loving heart.”

Ada Todd saved those letters, symbols of devotion from her husband, James Todd, a fair-skinned black man from Baltimore who worked as a Pullman porter in the late 1800s, and spent weeks and sometimes months away from home.

His earnings allowed the family to move from a cramped, predominantly African-American section of Vinegar Hill in Brooklyn to a more residential street in Bedford-Stuyvesant, to a spacious 11-room house in Flushing, Queens. It was only when he was dying in 1901 that Ms. Todd finally began to piece together the truth: Her husband was not from Baltimore. He was not a Pullman porter. And he was not a black man…

…Yet 19th-century history is dotted with such cases. White men and women driven by love, ambition or other circumstances sometimes leapt across the racial chasm, defying state laws and social conventions designed to keep blacks and whites apart.

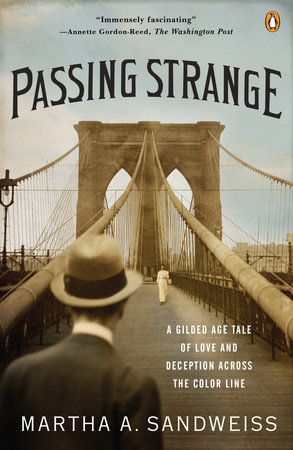

“We’ll never know how many people did it,” said Martha A. Sandweiss, a historian at Princeton University who documented Mr. King’s double life for the first time in her book “Passing Strange,” which was published in 2009.

“If they did it well,” she said, “they’re invisible.”

Clarence King did it well…

Read the entire article here.