Pink and the Fancy Gal: White Slavery, the Abolitionists’ Crusade, and the Painter’s CanvasPosted in Articles, History, Literary/Artistic Criticism, Slavery, United States on 2016-11-29 01:35Z by Steven |

Pink and the Fancy Gal: White Slavery, the Abolitionists’ Crusade, and the Painter’s Canvas

Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide: a journal of nineteenth-century visual culture

Volume 15, Issue 3, Autumn 2016

Naurice Frank Woods Jr., Assistant Professor of African American Art History; Director of Undergraduate Studies in the African American and African Diaspora Studies Program

University of North Carolina, Greensboro

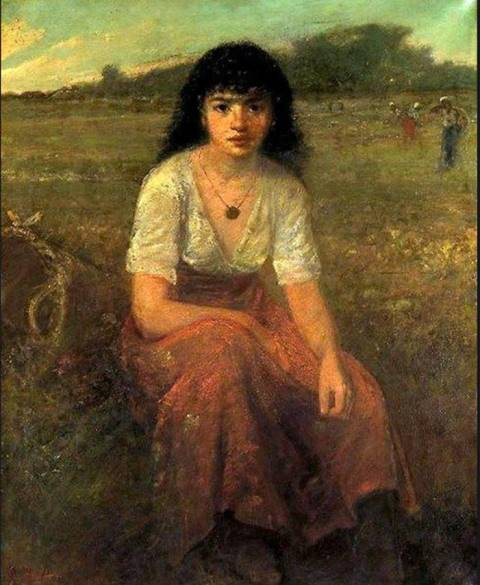

Fig. 1, George Fuller, The Quadroon, 1880. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift of George A. Hearn, 1910. |

This article examines two paintings from the antebellum period, The Slave Market (ca. 1859) by an unidentified artist and The Freedom Ring (1860) by Eastman Johnson, which involve the purchase of nearly white slaves, and attempts to delineate the motivation for presenting these images before the public. These paintings functioned much as slave narratives, and abolitionists used them to provide visual evidence of an insidious, often sexually depraved side of “the peculiar institution.”

In late 1849, Massachusetts native George Fuller (1822–84) traveled throughout the Deep South in pursuit of portrait commissions.[1] Like many of his northern contemporaries, Fuller sought a receptive and less competitive climate below the Mason-Dixon Line. The artist’s journey placed him directly in the midst of a region addicted to the institution of slavery, and while it may not have been his intention to observe astutely the lives of human chattel, Fuller was increasingly aware of their plight and recorded his observations in a sketch diary. Fuller’s drawings and subsequent commentary revealed neither his political inclinations about the “great divide” that was gripping the nation nor his moral position on the subject. This was, however, his third trip to the region, and while his sketches remained dignified depictions of black plantation life, his words reflected growing concern over certain “rituals” conducted in the South.

One of these rituals, a slave auction involving a beautiful quadroon, affected him profoundly. Fuller had witnessed slave auctions before, but the sight of men bidding over a nearly white slave like a farm animal caused him to write:

Who is this girl with eyes large and black? The blood of the white and dark races is at enmity in her veins—the former predominated. About ¾ white says one dealer. Three fourths blessed, a fraction accursed. She is under thy feet, white man. . . . Is she not your sister? . . . She impresses me with sadness! The pensive expression of her finely formed mouth and her drooping eyes seemed to ask for sympathy. . . . Now she looks up, now her eyes fall before the gaze of those who are but calculating her charms or serviceable qualities. . . . Oh, is beauty so cheap?…

Read the entire article here.