Mat Johnson: Black & White & Read All OverPosted in Articles, Interviews, Literary/Artistic Criticism, Media Archive, United States on 2016-03-08 01:06Z by Steven |

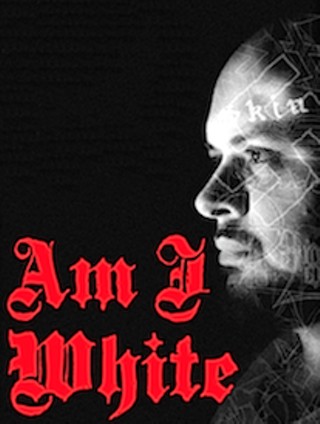

Mat Johnson: Black & White & Read All Over

The Austin Chronicle

Austin, Texas

2015-06-18

Our interview with the Houston-based author

This is an interview with Mat Johnson, who wrote the acclaimed Pym – which is somehow a popular favorite and a cult favorite, simultaneously, we’d swear – and who is most recently author of the novel Loving Day, which we’ve reviewed right here, just out via the Spiegel & Grau imprint of Penguin Random House.

Note: Johnson had written a few books before those two, yes, and – here, that’s what this link (thank you, Wikipedia) will tell you all about. And here’s the interview:

Austin Chronicle: Your Pym was one hell of a wild ride, like a fantasy thriller crossed with cultural critique, and it seemed to go all over the map. An interesting map, and hilariously drawn, but with so much stuff, like, galloping through the story. Loving Day, funny as it is, seems a lot more focused and relatively subdued.

Mat Johnson: The type of work I’ve been doing has its limitations and its strengths. And one of the strengths, I think, letting it go half wild allows me to take it to places I wouldn’t have if I was planning it meticulously. So I realize that, basically, I’ve been throwing knuckleballs. You know? You throw a knuckleball, there’s an acceptance that you’re dealing with chaos, but, hopefully – through technique and through practice – you can manage to control chaos enough to get it into the general direction. And that’s been the trick. Of course, the question is: How do you follow it up? And I don’t know if I can! [laughs] With Loving Day, what ended up being the entire book, I had imagined it as half of the book – but thank God I didn’t go on for another 300 pages. When I started it, I was interested in looking at mixed identity, mulatto identity – which, almost always in literature, is an I, singular – “This is my experience, I’m different than everybody,” and that’s the tragic mulatto archetype. And so what I wanted to do was try and say, “Okay, this is a different time, now – it’s more of a we.” What does it mean when you take something that’s so often been described as an individual experience and you start looking at it as a group experience? That was one of the original impetuses – there were a couple of them. Another was just, I wanted to write about Philly. [laughs] And the other one was that line, that opening line, “In the ghetto there is a mansion, and it is my father’s house.” And I really liked that line, and I caught myself saying it to myself – like it was lyrics to a song – and I thought, “Oh shit, this is something. Why is this interesting to me?” Because sometimes it’s my subconscious that’s interested, and my conscious has to figure out why my subconscious cares. So it built from there. And ultimately, while I was writing it, I realized that the father-daughter story was the essential story. And so, once I had that, that’s when I had my structure…

…AC: Okay, here’s a, uh, a Tricky Race Question. There are all these wrap-ups you see in the media – The Best Of The Decade, The Best Of The Century, and so on. The Best Black Writers Of blah-blah-blah. And not that it’s a zero-sum game, but there’s gonna be some list of The Top Ten Black Writers, and if you’re on that list? And there’s some other writer, who’s almost as good as you are – like it could be gauged that precisely, so they’re definitely next on the quality tier – but you’ve knocked them out of that top ten. And they’re not mixed, they’re black. Are they gonna feel like, looking at you, “Wait a minute, what is this dude doing on the list?”

MJ: Yes, they will feel like that. Because one of the things, in the larger sense of Who Gets To Get Listened To? Part of the reason we have these lists – of The Top Ten African-American Writers or The Top Ten Latino Writers – is because when it’s just The Top Ten Writers? It’s actually The Top Ten White Writers, and with maybe one or two other kinds of people thrown in to, you know, integrate it. So the initial problem is that the black writers’ response, other ethnic writers’ response, is to the fact that there’s really a kind of antiquated segregation in publishing. So that’s part of it. The other part is, there’s not a lot of black writers writing literary fiction, so you’d have to get it down to about The Top Five, probably. [laughs] But one of the things that’s difficult for writers of color is that your success is largely based on a white audience, so people who have sort of an in into the larger white mainstream are going to get more attention. Now, sometimes those ins are, you know, white readers are interested in getting a kind of inside look into a culture that’s unfamiliar to them. And sometimes those ins are like with Loving Day – there’s my Irish father, and it’s Irish this and Irish that – so that’s also an in that kind of puts a sign on the door that says White Money Accepted Here Too. You know?…

Read the entire interview here.