A Critique of Pure Pluralism

Chapter in:

Reconstructing American Literary History

Harvard University Press

1986

386 pages

ISBN-10: 1583484167; ISBN-13: 978-1583484166

Edited by:

Sacvan Bercovitch, Powell M. Cabot Research Professor of American Literature

Harvard University

pages 250-279

Chapter Author:

Werner Sollors, Henry B. and Anne M. Cabot Professor of English Literature and Afro American Studies; Director of the History of American Civilization Program

Harvard University

Men may change their clothes, their politics, their wives, their religions, their philosophies, to a greater or lesser extent: they cannot change their grandfathers.

Horace Kallen

Reviewing the new (fifth) edition of James D. Hart’s Oxford Companion to American Literature, Joe Weixlmann praises the editor’s effort to expand the coverage of black authors, yet finds the volume’s treatment of black, ethnic, female, and modern writers ultimately insufficient and wanting. Weixlmann concludes that “the old, venerable Oxford Companion to American Literature, despite its partial facelift, remains in its current incarnation, a product of such staid American and academic values as racism, sexism, traditionalism, and elitism.”

This identification of deplorable omissions with a scholar’s bias is quite common in the current debates. Frequently an opposition is constructed between closeminded narrowness (sexism, racism, elitism) and the alternative of inclusive openness associated with what is often called “cultural pluralism. In his essay “Minority Literature in the Service of Cultural Pluralism,” included in one of the several Modern Language Association readers on American ethnic literature which were published in the last decade, David Dorsey writes:

Only from the diverse literatures can youth feel the meaning of the past … At present diversity is everywhere tolerated in theory, punished in practice, and nowhere justified or justifiable beyond an appeal to solipsism. But America has no choice. Only a genuinely pluralistic society can henceforth prosper here. It must be nurtured in our diverse hearts. And for that we need literature, which is the language of the heart.

In this scholarly drama of diversity and pluralism versus traditionalism and prejudice there is emotion and prophecy just as there are heroes and villains. The editors of another MLA reader, Ethnic Perspectives in American Literature (1983), write:

Ethnic pluralism, once the anathema to those who espoused the melting-pot theory, has become a positive, stimulating force for many in our country . . . Transforming the national metaphors from “melting pot” to “mosaic” is not easy. Indeed, the pieces of that national mosaic have been cemented in place with much congealed blood and sweat. We must all continue to work at making the beauty of our multiethnicity shine through the dullness of racism that threatens to cloud it…

…The dominant assumption among serious scholars who study ethnic literary history seems to be that history can best be written by separating the groups that produced such literature in the United States. The published results of this “mosaic” procedure are the readers and compendiums made up of diverse essays on groups of ethnic writers who may have little in common except so-called ethnic roots while, at the same time, obvious and important literary and cultural connections are obfuscated. As James Dormon wrote in a recent review of such a mosaic collection of essays on ethnic theater, “there is little to tie the various essays together other than the shared theme ‘ethnic American theater history,’ as this topic might be construed by each individual author.” The contours of an ethnic literary history are beginning to emerge which views writers primarily as “members” of various ethnic and gender groups. James T. Farrell may thus be discussed as a pure Irish-American writer, without any hint that he got interested in writing ethnic literature after reading and meeting Abraham Cahan, and that his first stories were set in Polish-America—not to mention his interest in Russian and French writing or in Chicago sociology. Or, conversely, Carl Sandburg may be dismissed from the Scandinavian-American part of the mosaic for being “too American.”

Taken exclusively, what is often called “the ethnic perspective”—which often means, in literary history, the emphasis of a writer’s descent—all but annihilates polyethnic art movements, moments of individual and cultural interaction, and the pervasiveness of cultural syncretism in America. The widespread acceptance of the group-by-group approach has not only led to unhistorical accounts held together by static notions of rather abstractly and homogeneously conceived ethnic groups, but has also weakened the comparative and critical skills of increasingly timid interpreters who sometimes choose to speak with the authority of ethnic insiders rather than that of readers of texts. (Practicing cultural pluralism may easily manifest itself in ethnic relativism.)

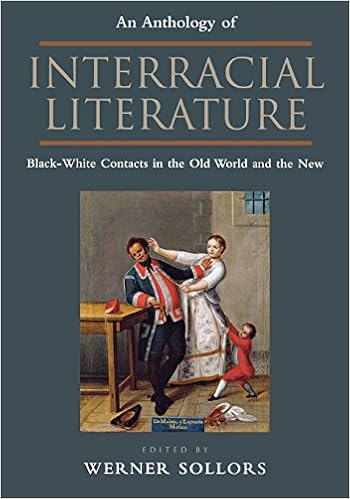

Yet, if anything, ethnic literary history ought to increase our understanding of the cultural interplays and contacts among writers of different backgrounds, the ethnic innovations and cultural mergers that took place in America; and the results of the critical readings should not only leave room for, but actively invite, criticism and scrutiny by other readers (“outsiders” or “insiders”) of the texts discussed. This can only be accomplished if the categorization of writers—and literary critics—as “members” of ethnic groups is understood to be a very partial, temporal, and insufficient characterization at best. Could not an openly transethnic procedure that aims for conceptual generalizations and historicity be more daring, profitable, and conceptually illuminating than that of simply adding to the sections on “major writers” chapters on “the popular muse,” “Negro voices,” “the immigrant speaks,” “generations of women,” “mingling of tongues,” and the rest of it?

Is it possible now to rewrite Quinn’s chapter and include Douglass or do we need separate chapters for each ethnic group, to be written by “insiders”? Can we construct a chapter on intellectual life in the early twentieth century in which ideas entertained by Anglo-American, Irish-American, Jewish-American, and Afro-American figures can be discussed together, or do we have to separate men and women, immigrants and American-born authors? Is it possible to connect Alain Locke, who ended his introduction to The New Negro (1925) with the hope for “a spiritual Coming of Age” with his college classmate Van Wyck Brooks, or are two heterogeneous ethnic experiences at work in them? These questions apply not only to the synchronic analysis of a period, but also to the construction of diachronic “descent lines.” Do we have to believe in a filiation from Mark Twain to Ernest Hemingway, but not to Ralph Ellison (who is supposedly descended from James Weldon Johnson and Richard Wright)? Can Gertrude Stein be discussed with Richard Wright or only with white women expatriate German-Jewish writers? Is there a link from the autobiography of Benjamin Franklin to those of Frederick Douglass and Mary Antin, or must we see Douglass exclusively as a version of Olaudah Equiano and a precursor to Malcolm X? Is Zora Neale Hurston only Alice Walker’s foremother? In general, is the question of influence, of who came first, more interesting than the investigation of the constellation in which ideas, styles, themes, and forms of travel.

In order to pursue such questions I have set myself a double task. I shall review significant criticisms of the shortcomings of the concept of cultural pluralism in the hope that the arguments made by intellectual historians of the past decade may affect thinking about American literature today; and I shall attempt to suggest the complexities of polyethnic interaction among some of the intellectuals who were involved in developing the term “cultural pluralism.” It is ironical that the story of the origins of cultural pluralism I shall tell could not have been told in the “pluralistic mosaic” format of group-by-group accounts of American cultural life: one protagonist would illustrate what the current fashion calls “the Jewish experience,” another “the Black experience,” a third “the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant experience.” But the fact is that it was not any monoethnic “experience” that led to the emergence of the concept of cultural pluralism. It was the protagonists’ troubled interaction with each other. Pluralism had a fairly monistic origin in a university philosophy department in the first decade of this century; yet it is a notion whose very mobility challenges the concept’s central tenet of the permanent power of ethnic boundaries…

Read the entire chapter here.